Her lymphocytes now grew continuously in culture and were positive for EBV antigens. Her rubella antibodies were negative but her heterophile antibody test, which had been established as the laboratory method of choice to diagnose infectious mononucleosis, 11 was positive. Her physician's clinical impression was rubella versus infectious mononucleosis. 8, 10 She became ill in August 1967 and missed 5 days of work.

A technologist working in the Henle laboratory who lacked antibodies against EBV regularly donated lymphocytes for EBV transmission/transformation experiments but her cells never survived in culture. Now comes a truly ‘once-upon-a-time' story. 8 As Hummeler's laboratory had been recently dismantled because of lack of funds, he brought the cells to the Henle laboratory, which was also in Philadelphia, where Epstein's discovery of a new herpesvirus was quickly confirmed, 9 and additional studies launched to further characterize this virus. 7 ‘As a last resort,' Epstein sent the Burkitt cells to Klaus Hummeler in Philadelphia, who had just spent a sabbatical with Epstein. Epstein believed that another laboratory should repeat his finding, but British virologists were not interested in collaborating. 6 in 1964 using electron microscopy to detect the virus in cultured Burkitt lymphoma cells. 5 Indeed, its etiology remained a mystery until 1967 when a serendipitous event established the causal relationship between infectious mononucleosis and EBV.ĮBV was discovered by Epstein et al. Infectious mononucleosis was recognized as a unique disease in the 1880s by Nil Filatov, a Russian pediatrician, who called the syndrome ‘idiopathic adenitis. Identification of EBV as the cause of infectious mononucleosis Future research goals are development of an EBV vaccine, understanding the risk factors for severity of the acute illness and likelihood of developing cancer or autoimmune diseases, and discovering anti-EBV drugs to treat infectious mononucleosis and other EBV-spurred diseases. There is no licensed vaccine for prevention and no specific approved treatment.

In addition to causing acute illness, long-term consequences are linked to infectious mononucleosis, especially Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple sclerosis.

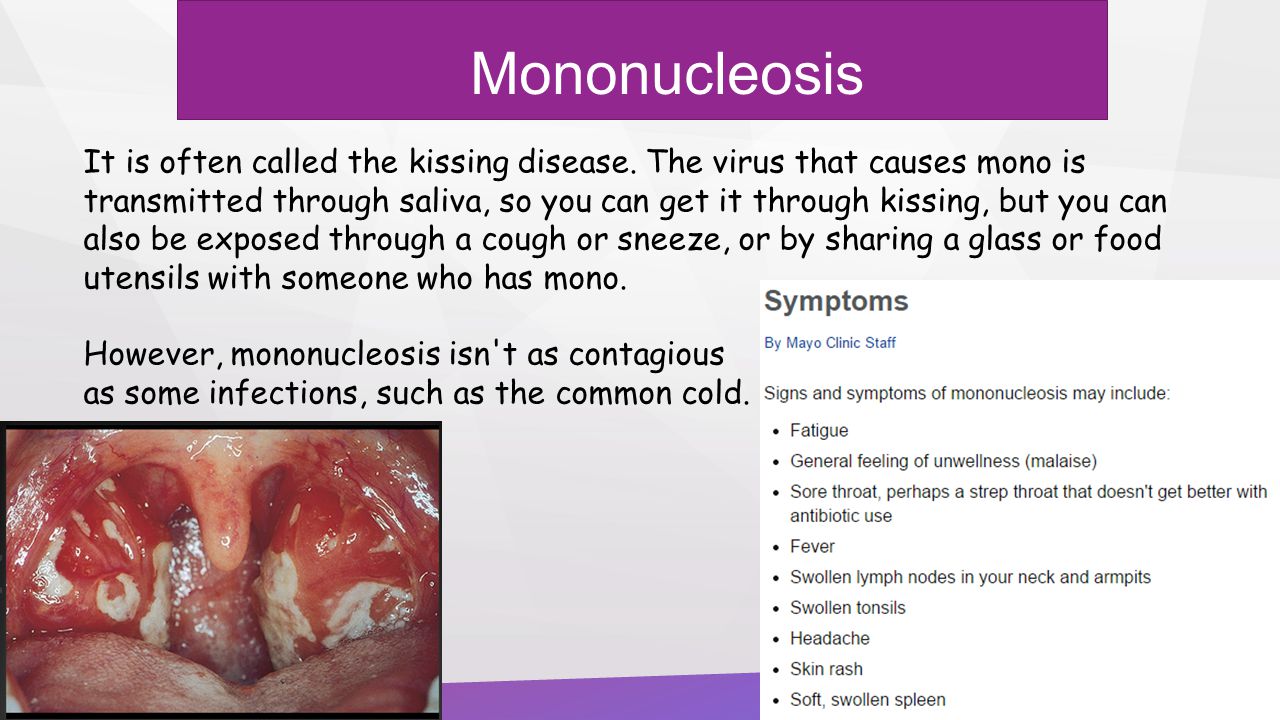

EBV-specific antibody profiles are the best choice for staging EBV infection. A typical clinical picture in an adolescent or young adult with a positive heterophile test is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis, but heterophile antibodies are not specific and do not develop in some patients especially young children. During convalescence, CD8 + T cells return to normal levels and antibodies develop against EBV nuclear antigen-1. The acute illness is marked by high viral loads in both the oral cavity and blood accompanied by the production of immunoglobulin M antibodies against EBV viral capsid antigen and an extraordinary expansion of CD8 + T lymphocytes directed against EBV-infected B cells. During the incubation period of approximately 6 weeks, viral replication first occurs in the oropharynx followed by viremia as early as 2 weeks before onset of illness. The virus is spread by intimate oral contact among adolescents, but how preadolescents acquire the virus is not known. EBV, a lymphocrytovirus and a member of the γ-herpesvirus family, infects at least 90% of the population worldwide, the majority of whom have no recognizable illness. Infectious mononucleosis is a clinical entity characterized by pharyngitis, cervical lymph node enlargement, fatigue and fever, which results most often from a primary Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)